The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge kindly hosted us for our final study day of 2023, which focused on how museums and heritage organisations are dealing with challenging legacies of colonialism.

Our first speaker was Matthew Platt, Assistant Curator of North Hertfordshire Museum, who reflected on his own experiences of the challenges of uncovering and dealing with the dark histories of some of the objects in museum collections. We are used to hearing about the challenges that larger museums may face, but these same challenges are often present in smaller museums too, who have to face them with very limited resources. In the case of the objects Matt highlighted, the approach taken has usually been to add information to the catalogue, and carefully consider whether and how an object should be displayed.

Next Katrina Dring told us about the stores move project at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. The project is providing a unique opportunity to reassess and make changes to the museum’s documentation procedures, including changes intended to address colonial violence, reintroduce and amplify the voice of originating communities, and make collecting history more transparent.

Jack Ashby, Assistant Director of the Cambridge Museum of Zoology then told us about his work researching the colonial histories of natural history specimens. Jack’s presentation had two areas of focus – how we can make the (sometimes violent) origins of natural history objects clearer, and how we can acknowledge the contributions of a wider range of people to scientific achievements. One result of this work is an online resource on the Colonial Histories of Australian Mammal Collections in Cambridge.

Our final speaker of the morning was Matt Cooper, Senior Listing Adviser for Historic England (East of England), and Regional Lead for contested heritage. There are over 400,000 entries on the national List of historic sites and buildings. Many have direct connections to empire and other contested aspects of our past. Matt shared some recent examples where listing casework was confronted by colonial legacies. For a while now celebratory information has been added when places have been listed because of their associations with people rather than because of their architectural features. This is harder to do when the association is a negative one. These histories are often complex and nuanced, and there isn’t space in a list entry to include all of the necessary detail. The approach Matt described aims to give the reader information that there is more to know without overwhelming the List entry. Historic England are also proactively seeking sites that colour in more of the picture of the past than just the white British experience, for example listing the gravestone of Joseph Freeman, who liberated himself from enslavement in the USA and made a new life in Chelmsford, Essex.

In the afternoon we were lucky enough to be given a tour of the Fitzwilliam’s exhibition Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance by curator Vicky Avery.

The Fitzwilliam Museum’s origins are in a vast donation made by Richard Fitzwilliam to the University of Cambridge in 1816. Fitzwilliam’s fortune was derived from that of his grandfather, Sir Matthew Decker, a founder of the South Sea Company in 1711, which trafficked enslaved people.

The exhibition takes place in the oldest part of the museum, the Founder’s Building. Usually temporary exhibitions are staged in a more modern building, the team wanted this one to be in the original building. This has brought logistical challenges (such as the location of digital features being constrained by the location of plug sockets) but means that the exhibition takes place at the heart of the museum.

The exhibition covers a lot of ground, from showing the connections Cambridge has to Transatlantic slavery to the ways enslaved people resisted oppression.

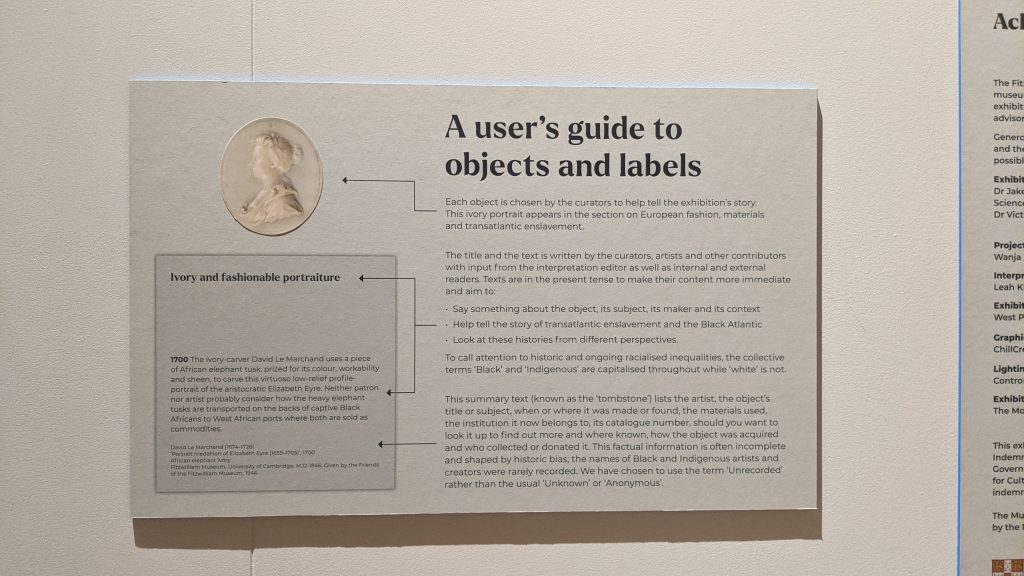

A key theme of the exhibition is whose stories get told and why. The first things the visitor sees when entering the space are two portraits. Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit is juxtaposed with a portrait of a young Richard Fitzwilliam. This sets the tone for further exploration of the theme about what is recorded and what has gone unrecorded.

As part of the exploration of what has been recorded and what has not, object labels include information on the origins of objects.

The exhibition combines historic objects with contemporary responses to the history and legacy of the Transatlantic slave trade. You can listen to an interview with one of the contemporary artists whose works feature in the exhibition in this video on the Fitzwilliam Museum’s YouTube channel:

The exhibition was described as the beginning of some very hard soul-searching about what a museum should look like in the 21st century. Further related exhibitions and activities are planned. The exhibition ends with a large space given over to audience feedback. A sectioned-off space contains a range of reference books, and several questions to prompt feedback. The comments being received are often very in-depth and will help to inform future work.